Homejoy, the San Francisco-based on-demand home cleaning startup announced it will shut down on July 31st, leaving customers who have already paid for services to request refunds while Google has swooped in to hire the company’s development team for its own on-demand marketplace, according to re/code. What happened to Homejoy, which has raised more than $39.7 million in venture capital, including from Google?

Co-founder Adora Cheung told re/code that the primary reason for abandoning the business is a clutch of lawsuits against the company by contractors seeking expenses associated with performing Homejoy jobs. The 1099 worker v. employee regulatory debate is certainly a factor, but it doesn’t explain the apparently sudden demise of a promising company. For weeks, rumors of a sale swirled and it is clear that the investors shut their purses. Anyone investing in this market has to have factored in the cost of regulatory battles, and we suspect that the proliferation of vertical home cleaning markets rushing into the space has demonstrated to investors that mere facilitation of transactions is not sufficient to ensure brand success.

On-demand market companies cannot keep house cleaners, home repair or plumbing talent engaged if they see their work being rewarded minimally while company employees get a full suite of benefits and other perquisites. Improving these low-income workers’ options in work, whether providing greater flexibility, better planning of work time or higher wages for being available “on-demand” must be addressed by on-demand startups. These firms must live and die on 20 percent or less of the total value of services they facilitate, and must show the talent at the edge of the network that they are in service to labor and customer alike. Uber is seeking to increase it share of transaction to 30 percent in several cities, which we don’t believe is sustainable because it leaves too little for the driver to prosper — more to the point, a $16-an-hour wage is not enough to feel prosperous while “this guy named Travis,” as an Uber driver called CEO Travis Kalanick on a recent ride, “is making billions.” Kalanick is now estimated to be worth $5.3 billion.

Homejoy did a good job of telling customers the stories of housecleaners turned freelance professionals, but they failed to make enough maids prefer HomeJoy to other channels. HomeJoy’s value proposition, that a pro would clean your house for $20 an hour, emphasized price over quality and assumed the maid/household worker is interchangeable. They were paying $12 to $15 an hour, slightly above the national average for maids.

Before the on-demand market can disrupt consumer lifestyles, it has to disrupt the employment options for the workers it would send to customers’ homes.

After searching the company’s history a bit, I saw David Hasselhof on the company’s blog — he was doing surprise housecleanings in New York for Homejoy this past Spring. Mr. Hasselhoff’s minimal appearance fee is $50,000. When Hasselhof, or someone like him, appears in a corporate history, the budget is out of control. Thinking back about the hiring message for the company’s Bay Area employees, which featured the usual perks of a San Francisco workplace, it is clear that one of the problems was HomeJoy had a lot of money and spent it too fast.

The company’s last round, $38 million, closed in December 2013. If there is less than $5 million left, we can extrapolate a burn rate of $1.7 million a month. HomeJoy had more than 100 employees in its headquarters and had expanded into related home services and the UK market. Management probably saw this as reacting to the pressures of competition, but it is a common mistake to fail to focus all available resources on key business problems, and Homejoy never mastered the labor relationship.

We recommend a rule of thumb for on-demand companies: Limit hiring based on labor engagement to a ratio of 1:80 or more. At Homejoy, that ratio would have provided revenue per FTE of around $320/hr., if those 80 maids were working full-time. This forces management to concentrate on growing its supply-chain (winning workers to their service) to justify additional FTE expenses while providing employees clear guidance that getting more productivity out of the available supply is their primary job. Everything needs to be directed to building the success and prosperity of workers in an on-demand market, otherwise those workers will leave or, worse, sue.

Homejoy is apparently out of money to fight legal battles, yet it is certainly a case that regulation did not kill Homejoy single-handedly. Customers are told explicitly on the HomeJoy FAQ page that “unfortunately” (a word used seven times on the page) they will need to file a claim for a refund and have no other recourse. This is not an orderly wind-down. Google has already indicated the Homejoy platform will be abandoned. Homejoy apparently also did not budget based on the advice that a startup must approach product with the intent to “build it and launch, then throw it away and build the right product based on what you learned from Version 1.0.” Newcomers to the market-building space are already using vastly improved tools — many of the next-generation tools, such as BreezeWorks and IntellaSphere, are aimed at supporting individual workers competing in many marketplaces.

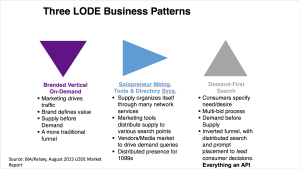

At BIA/Kelsey NOW, in June, we laid out the three business models Local On-Demand services are likely to follow. Branded destinations are the most familiar, operating using many of the same metrics as a traditional media company, emphasizing traffic growth and content over the labor delivered. By contrast the “Solopreneur” marketing tools category emphasizes improved billing, customer engagement and customer-worker relationships over customer-brand relationships. The labor-centric markets may be the on-demand sweet spot.

Ultimately, Homejoy’s collapse is a failure to recruit on-demand workers on terms they will embrace. HomeJoy earned just a three-star rating on the career site GlassDoor, reflecting its failure to engage workers — at “three” isn’t transformative, it’s the status quo. Marketing spending, even on The Hoff, doesn’t impress the house cleaner if it doesn’t fill their pockets. Investors may back away from some on-demand companies as a consequence of the Homejoy shuttering, which would probably be good for the current pack of on-demand companies, who need to learn to live lean, like the people who do the actual work in the local home cleaning market. When everyone is profiting, the wealth will come to entrepreneurs and VCs who are patient.

BIA/Kelsey take: Yes, some investors will likely shy away from on-demand until the workforce regulations are decided. Building an on-demand brand will require greater investment in the worker relationship to justify the “piecework” approach to pay. By the time the legal issues are worked out by politicians and in the court of public opinion, it will be commonplace for workers to list their services in many marketplaces rather than just one branded one. There is no doubt that work is changing due to the close logistical management made possible by data networks, and that companies will seek to pay only when productive work is being accomplished. Of course, paid work is more profitable than when workers are idle. Why then the focus on the traditional hourly wage, which was created to keep workers on staff and available to do work when it was available, when talking about compensating workers when their labor is of the highest value? Vertical services, like Homejoy and Uber, will be hard-pressed to compete without recognizing that their workers’ experiences are just as critical to success as each customer’s experience. For a marketplace operator, everyone is a customer. The answer isn’t simply to pay more, but to provide a better deal for workers who deliver great customer outcomes.

This Post Has 0 Comments