How big can the Local On-Demand Economy get? We’ll be examining this question in several blog posts this week as we prepare for BIA/Kelsey NOW, which happens June 12th at the Mission Bay Conference Center in San Francisco. Use the discount code “MR100” to save $100 on tickets. Will you be there?

BIA/Kelsey estimates that in 2015 the total addressable market for in-home on-demand services, including shopping time, travel and child/elder care, is 22.8 billion hours of currently unpaid household work, representing approximately 3.5 percent of total household work, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Time Use Survey. Using the reported average income of “1099 workers” from several sources of approximately $17 an hour, the total market this year, if fully engaged, could be worth up to $465 billion. At the current industry standard, a 20 percent share for the on-demand marketplace operators who connect customers and contractors, on-demand companies’ revenues potentially could be worth $93 billion in 2015.

We believe 2015 actual market penetration by on-demand companies appears, based on reported and leaked revenue data from various on-demand companies, to be approximately $18.5 billion, or 3.9 percent of total addressable market. Much of that revenue is captured in transportation, particularly by Uber, which is expected to book more than $10 billion in ride revenue in 2015. Note that Uber ride revenue includes drivers reported 80 percent share, giving Uber total fees of approximately $2 billion this year.

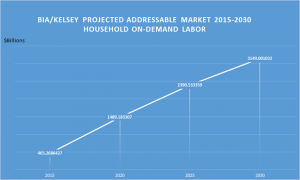

In short, there is 96.1 percent of a market unclaimed and it will grow at a compound annual rate of 13.50 percent through 2030 based on projected population growth and an increase in average on-demand earnings of 2.33 percent per year over that time, from $17-an-hour to $24-an-hour.

For now, Uber represents more than half of the revenue of organized 1099 labor. Much of Uber’s revenue comes from business travel, which is not included in the home services market, but it does claim considerable personal travel in cities where it is well known. Its rapid ascent suggests that similar growth could occur in any area where people have access to ad hoc networks of people and resources. Many of the carpools, childcare arrangements, cooking and helping services provided by neighbors to neighbors will be ingested into the formal economy through LODE organizations.

The household services market

Billions have been invested in home services companies in pursuit of work currently performed in the home by household members. In-home services, such as TaskRabbit, HomeJoy and InstaCart, cannot generate revenue if their offerings are too expensive for middle class households to replace with more profitable work in or out of the home. Affluent households can add these services at will, but their adoption of on-demand services will not deliver substantial economic growth, because workers must be able to afford to do contract work while substituting for their unpaid labor at home if there is to be a thriving market for local experience and services.

The rhetoric of LODE paints a vivid picture of on-demand workers busily exchanging services, sharing burdens while doing the jobs they most enjoy — it’s a promise on-demand companies are making to their prospective contractors. For example, a car to take the kids to school cannot cost $17 an hour for a mother making $12 an hour working at another task as an on-demand worker. If LODE home service workers are expected to adopt on-demand services as well as provide them, their earnings must exceed the cost of doing their own work at home.

The U.S. economy produced $16.77 trillion in GDP during 2013, the last year for which complete data is available. However, the calculation of GDP does not include unpaid household work. If it did, U.S. GDP would be several trillion dollars higher than it is reported today. Organizing this labor to bring it into the formal economy at a reasonable price with reasonable wages is the challenge to LODE companies if they expect to profit. That cannot be done while strangling the golden goose of ad hoc skilled and low-skilled labor with lower wages. Ultimately, both unpaid household labor and the work that can be exchanged for other services are essential to the economy, its time we counted both.

Household labor projections, 2015 – 2030

BIA/Kelsey has developed a model for projecting the addressable revenue in the home based on the householder’s ability to pay for services that they may forego doing themselves to make time for paid work in another area of their expertise. With reasonable and rising wages, household on-demand work can add up to $3.1 trillion to the U.S. economy by 2030 simply by formalizing transactions.

The long process of recognizing the value of work that contributes to the whole economy has ignored the unpaid work performed in the home by household members, particularly mothers. During the child-raising years, women doing unpaid household work an average of 32.4 hours each week on food preparation, cleaning, laundry, household management, shopping and more than 10 hours caring directly for children or adults. Men, by contrast, average 17 hours of unpaid household work each week, 60 percent of which involves food preparation and lawn care. Many of the questions about the future of work in the face of automation and robotic replacements for human labor will revolve around how to recognize the value of human engagement. Suggestions about a “guaranteed income,” recently floated by author Martin Ford in Rise of the Robots, among others, reflect how contributions to raising productive and engaged citizens will become compensated in the future.

Our research suggests that creating markets can, if they provide genuine incentives for doing great work, catalyze organized work in a variety of niche markets that previously existed in the dark economy, the work and exchanges that are not currently accounted for in a corporate profit and loss statement. Making “1099 labor” a cost within an on-demand company’s books blesses and confirms its value in the market.

Building from the Census’ American Time Use Survey, which describes in detail the activities that Americans do to support their home’s daily needs, BIA/Kelsey estimated the total number of hours of work currently performed without pay in the following categories:

- Food & drink preparation

- Cleaning

- Laundry and sewing

- Household management

- Lawn and garden care

- Maintenance and repair

- Caring for and helping household members (including eldercare)

- Caring for and helping household children

- Grocery shopping

- Travel related to unpaid household work

All these categories contribute to the overall estimated value of the on-demand household market in 2015. In the next posting, we’ll dig into the home cleaning and laundry markets, providing total and addressable market sizes. You’ll be surprised how many billion-dollar companies could be supported, if on-demand labor is given its chance at prosperity, too.

We estimate that 18 percent of the U.S. population can conveniently access local on-demand services today, mostly in the central cores of major metropolitan areas. Based on an April 2015 report by PricewaterhouseCoopers, “The Sharing Economy,” which found that 19 percent of internet users have tried an on-demand service — which we believe overstates the share of the population that can access these services because poor and unemployed people endure much lower connectivity rates — we have high confidence that our 18 percent addressable market estimate is sound.

Additionally, we adjusted the resulting hours of addressable on-demand labor by subtracting the U6 unemployment rate, which includes underemployed and frustrated workers who are highly unlikely to purchase on-demand services, to arrive at the most conservative estimate of LODE hours worked and revenue. Interestingly, when unemployment exceeds 12 percent or wages fall below the exchange threshold at which a worker can trade one form of labor for another form of service, our model produces negative results.

Building on this model, we’ll be delivering the first of our Local On-Demand Economy Insight papers, detailing each of the categories of unpaid work that could be displaced by LODE, as well as sizing existing industries that are threatened by the on-demand approach, shortly after BIA/Kelsey NOW. Join us at the show.

This Post Has 0 Comments